Queen Máxima of the Netherlands and Zvi Hecker during the inauguration of the complex of the Koningin Máximakazerne for the Royal Dutch Military Police, Schiphol, Amsterdam Airport, Netherlands 2001–2018, Architect: Zvi Hecker in collaboration with Eyal Weizman, Copyright: DVD (Dienst Vastgoed Defensie)

An interview with architect and artist Zvi Hecker about the relation between the two disciplines, the search for an unforeseeable idea, the notion of home, and architecture of survival.

Zvi Hecker, you are an architect and an artist exhibiting in museums and international galleries. How do you deal with these two aspects of your activity? Are they separated, or two parts of one quest and creative production?

I consider architecture an art. I am an artist whose profession is architecture. In architecture I try to create a space, in painting an illusion of space. For me both activities are mentally inseparable. A good example of this interdependence was my exhibition in Nordenhake Gallery in Berlin in 2017 called “Crusaders Come and Go.” It dealt with gallery space using painterly means.

You once said that architecture and art often are in conflict with “legality”. What do you mean by this?

A real piece of architecture, because of its originality, is subversive and therefore seldom fits into building codes and legal restrictions. Eventually it broadens the legislative provisions and becomes absorbed into the mainstream tradition.

Spiral Apartment House, Ramat Gan, Israel, 1985-1989, Architect: Zvi Hecker, Copyright: Zvi Hecker Architect,

Photo: Michael Krüger

Jewish Cultural Centre, Duisburg, Germany, 1996-2000, Architect: Zvi Hecker, Copyright: Zvi Hecker Architect, Photo: Michael Krüger

Often your projects start with an image or a metaphor but not with a predefined form. The process of design is important for you. Could you explain that a bit further?

In every new project we are in search of its unforeseeable idea. Unfortunately its whereabouts are unknown and therefore cannot be reached by public transport. In order to reach this unknown destination, this idea, we have to build our own means of transport. For me, architectural sketches are such a vehicle, and the metaphors are this vehicle’s fuel.

Your projects seldom are singular buildings, but rather ensembles. What is the concept behind this?

You are right – for example, upon walking through the Jewish School in Berlin, many visitors get the impression that the school is like a small city. It has squares, streets and narrow passages. The same is true for the Koningin Máximakazerne in Schiphol; it is like a walled medieval city.

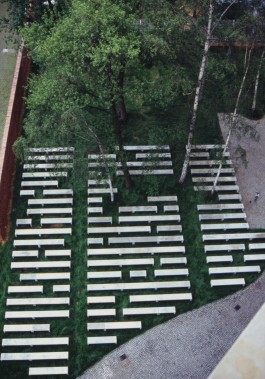

“Page” - “Ort der Erinnerung”, memorial site, Lindenstrasse, Berlin, 1997, Architect: Zvi Hecker, with Micha Ullman and Eyal Weizman, Copyright: Zvi Hecker Architect

Heinz-Galinski Jewish School, Berlin, Germany, 1991-1995, Architect: Zvi Hecker, Copyright: Zvi Hecker Architect, Photo: Michael Krüger

City Hall, Bat Yam, Israel, 1961-1963, Architects: Alfred Neumann, Zvi Hecker, Eldar Sharon, Copyright: Zvi Hecker Architect, Photo: Zeev Herz

Palmach Museum of History, Tel Aviv, Israel, 1993-1997, Architects: Zvi Hecker, Rafi Segal, Copyright: Zvi Hecker Architect, Photo: Michael Krüger

You were born in Krakow in 1931 and were deported with your family by the Russian Army first to Siberia and then to Samarkand. You studied and worked as an architect in Israel and you have lived and worked in Berlin for more than 25 years. What impression have these experiences left upon you? What does “home” mean for you? Is Berlin your home?

I was born in the medieval city of Krakow, spent much of my youth in medieval Samarkand and began my architectural career by building a medieval Karavan Sarai in the Negev Desert (the Israeli Military Academy). Since my architecture shares many concerns with the architecture of the Middle Ages, critics are inclined to presume that my biography is a clue for understanding my work. I am not so sure about that. Living and working in Berlin as a foreigner, who has felt welcome, I hope that my work, like the work of many artists, helps Berlin to assume its role as a cultural and political counterweight to other world centres.

In your experience, how far does the notion of “home” presuppose cultural identity? How is cultural identity defined today? Is it the task of architecture to express this cultural identity?

I can only speak for myself. Uprooted many times, I carry my roots with me. That is why in my work, one can see not only where I build but also where I come from.

Koningin Máximakazerne for the Royal Dutch Military Police, Schiphol, Amsterdam Airport, Netherlands 2001–2018, Architect: Zvi Hecker in collaboration with Eyal Weizman, zenithal view, Copyright: Google, DigitalGlobe

Ramot Housing, Jerusalem, Israel, 1971-1975, Architect: Zvi Hecker, Copyright: Zvi Hecker Architect

What are your thoughts about global political and social development as well as the increasing instability of today’s political and social structures?

We have already lost the illusions of progress and equality at the beginning of the 20th century. This idea resonated strongly with political programs and social doctrines spreading across Europe at the turn of 20th century: first by the Fascists in Italy, then by the Nazis in Germany, the Communists in Russia, and even by the Zionists in Palestine. All were eager to improve the “impure” Homo sapiens, just as much psychologically as physically. In Palestine, on posters from the 1930s, the ideal Jew could be mistaken for a tall Scandinavian – blond and blue-eyed, Marinetti and the Futurists claimed that pasta made Italians stupid and its consumption should be limited. The results of this experiments, as we know, were tragic.

What do these changes mean for an architect? How would you define the architect's task within society?

I have always been interested in the architecture of survival; architecture in extreme basic conditions. Architecture will come back to its basic function which is protection of humans, protection of life. This, in my opinion, remains the dominant theme of architecture, a concept entrusted to the responsibility of the architect.

Profil

Born in Krakow 1931, Zvi Hecker grew up in Samarkand, studied Architecture at Technion, Haifa, painting at Avni Academy, Tel Aviv, taught Architecture at Université Laval, Quebec, and Universität für Angewandte Kunst, Vienna. In 1960 he set up his practise in Tel Aviv and in 1991 in Berlin. Zvi Hecker has realised internationally acclaimed projects in Israel and Europe. His work is exhibited regularly in galleries and museums and it is part of the collections of Centre Pompidou in Paris, MoMA New York, Israel Museum in Jerusalem, Jewish Museum and Berlinische Galerie in Berlin. He lives and works in Berlin.

Zvi Hecker died in September 2023.

www.zvihecker.com

Cover portrait, Copyright: Arkadiusz Luba

Zvi Hecker, Photo: Oris 2017, Damil Kalogjera