C-Mine, theater & concert hall, tourist centre, design museum, Genk, Belgium, 2010, photo: Stijn Bollaert

An interview with Freek Persyn and Johan Anrys, founding partners of Brussels-based architecture office 51N4E about bridging the gap between an imagined and an actual reality, about the reuse of buildings, collaborative environments, architecture as a transformational process and the opportunities of change.

Freek and Johan, in Brussels you are realizing the ZIN project which will change two monofunctional 1970s towers – the so-called World Trade Center – into a multifunctional building. As such it is crucial in the transformation of the Northern Quarter of Brussels, which was imagined in the 60s as a pure-office neighborhood but failed entirely. Looking at the mistakes of the past and chances for the future: does your project include a general urban vision, spatially, socially?

Freek: Both the original WTC and the new project stand for a certain urban vision, and of course they are very different. A lot of things that were tried in the WTC didn’t succeed. It was a piece of a larger urban vision, but because the context around never appeared, it stood a bit on it’s own, missing what it was imagined for. An entire neighborhood was destroyed for this – and then only a few pieces were built. The failure was that there was really a gap between an imagined reality and an actual reality. The new project is meant to connect the pieces, to look at this failure and to somehow work within it. In that sense, it is not about replacing an older vision with a new one; it is more an attempt to deal with the remnants of that trauma.

You were part of the temporary use of the WTC that preceeded the current refurbishment and included also artists and subcultural organisations.

Freek: Yes. Moving there was indeed an attempt to bring the attention to the fact that these places still have a lot of opportunities. We organized workshops on-site, we gathered a community of people around us to inhabit that place, also treating it as a school, using it as an exhibition space, with many different parties getting involved. We tried to show that these buildings don’t have to get demolished; you do not have to start every 50 years all over again. When then at a certain point there was a competition, we were able to propose the idea that you could reuse those towers. But it is really going step by step, trying to bring an insight into the potential of the place. We are now busy with multiple sites in the North District where we try this idea of reusing. It is a challenging discussion: how much are you able to keep, how much do you have to replace?

Johan: In a way it is also from an aesthetic point of view a beautiful environment. When we went there with our office temporarily, I think we already believed somehow that this area could benefit from growing naturally towards more diversity again. In a way our intention was not primarily to come up with an architectural solution. It was more about: what can we do to bring back life on a 24h-level into this quarter?

Freek: Buildings that were monofunctional in the past don’t have to be used like that in the future. Today, architecture is still thought too much in certain typologies, for working, for living, and then these different types are combined. ZIN is more about the idea of adaptability: things can change, and that is offering a lot of opportunities.

Buda, exhibition & event facilities, artists’ studios, budalab, Kortrijk, Belgium, 2012, photo: Filip Dujardin

Buda, exhibition & event facilities, artists’ studios, budalab, Kortrijk, Belgium, 2012, photo: Paul Steinbrück

Would that be a general approach in your work – to question typologies and to open them up?

Johan: To integrate multiple perspectives is part of the dna of an office where you have a collaborative environment and not the handwriting of one person. So, yes, we are a bit intrigued by how projects get multiple lives. This is a social point of view, but it is also an ecological one. If we talk about sustainability, what we as architects can master best, apart from all the engineering, is creating permeability or multiplicity. In that sense, ZIN is a test case which, with an owner with a long term perspective, had the conditions for us to think about a building that is adaptable in time. It may absorb an evolution towards further diversity, in an area where there is no masterplan, no predicted future.

Freek: We rather use the term “multiple lives” and not “multiple functions” because functions are quite determined. And life is very undetermined. You imagine a building for multiple lives quite different than for multiple functions. Ideally, what will happen will be quite ambiguous.

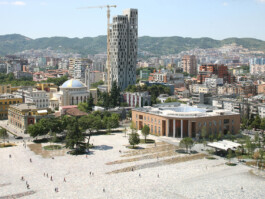

A while ago you also completed two projects next to each other in Tirana, Albania: the very central Skanderbeg Square and a tower next to it. Is it possible to transport a certain urban vision to a country which has a very different history and a very transformational present?

Freek: When we worked on the square we already had been busy for some time in Albania and had met a lot of people. And we were still rather young architects. In that sense we didn’t have a lot of experience to bring and more experience to gain. We were willing to propose things, but also to listen and to adapt. It was really like a journey.

Johan: You asked for our approach. Yesterday I talked to a client who said: you know why we want to work with you? Because you don’t come with architecture as a solution, you come with a process as a solution, and this will help us. That is actually what we try to do: to see architecture as a transformational process which helps people to explain their wishes and ideas, and to strive to come up with a solution that brings them closer to what they desire. It allows people to step into a process together, to make compromises. Compromise is not always less than what you dream of, it can be more than what you were ever able to dream. Skanderbeg Square, too, was a process, initiated by a mayor who wanted to give his city a symbol, a common square to share. When, after a period of severe communism, people were suddenly allowed to own things, what you could see were huge cars and beautiful houses – but completely careless environments. The biggest transformation in Tirana now is that people start to think about the quality of what they as a society share. The square is a symbol for that. It is important that people can enter a comfortable environment with green, silence, water, wind. But the fact that public authorities were able to realize such a public project, without corruption, and that the society was able to build it – that is the most important element. People begin to ask: why can’t we do something like that on another spot, too? This is how a mentality starts to change.

C-Mine, theater & concert hall, tourist centre, design museum, Genk, Belgium, 2010, photo: 51N4E

Skanderbeg Square, public space and cultural facilities, Tirana, Albania, 2017/2019, photo: Filip Dujardin

Speelpleinstraat, Kindergarten & greenery service, Merksem, Belgium, 2012, photo: Filip Dujardin

Speelpleinstraat, Kindergarten & greenery service, Merksem, Belgium, 2012, photo: Filip Dujardin

During the pandemic it became clear how important public space is – for people who do not have any private outside space, but also as an arena for political expression and demonstrations. Do you think that the perception of public space has changed, also in a political sense?

Freek: I think in Belgium politicians and policy makers exposed their view on how they see society. It is a very economical view, focused on keeping productivity running, but not so much on welfare and culture. Especially as, at the beginning of the lockdown, there was also a time when we were not even allowed to go outside in parks, so neither use of public space, private nor political, was possible at the time. A lot of politicians might live in houses with gardens somewhere in the Belgian countryside. But a lot of people in Brussels don’t live in these circumstances. Personally, I also live in a rather small apartment of around 80 m² and within the family you could already feel the tension sometimes. In some areas in Molenbeek or Anderlecht families live with 15 people in such a space. They need public space to live well, and that was totally neglected.

Johan: Where I live, a group of inhabitants started a project now to demineralise the street – for which we received subsidies by the Flemish government – and at the same time, together with a school next door, to work on the public space there. But people are not used to take initiatives like this. We have institutionalized everything, we are used to a public space which is designed, managed and divided into functional zonings. Of course, taking initiative is uncomfortable because once you do, you have to start to negotiate. Therefore I even understand why we as a society have chosen to organize it like that: it means less conflict. But it’s obvious that – with all the professional intelligence that a community has, with architects, urbanists, lawyers, economists etc. living in one neighborhood – you can have fantastic local projects. Here the city supports this with their knowledge. Sometimes they have to intervene, saying: these are the rules. But they are open to see what can be done. I am thrilled by this process.

How do you trigger civic initiatives and involvements?

Freek: In Tirana we had to propose a few examples to demonstrate how the square could work. People are more led by examples than by regulations. When they really see the opportunity they start to act themselves.

Johan: This touches another problem which is connected to the process of public tendering. The reason for this process is clear: to create a fair competition. But it destroys the engagement of the people in their own environment, it destroys our communities and cities. So again it comes down to collaborative processes that have to be installed to make that transformation. And this is political. Of course – we do live and work in a regulated economy, and without regulations procedures can easily be misused as well. But I believe we went a bit over the top at this point. You have to make up a balance and take a certain risk as a society. You have to enable engagements.

Our last question would have been if you, as architects, consider yourself as political actors in society. Emphasizing involvement and processes already gives an answer to this.

Freek: Yes. There is a desire to try to create conditions that we would like to be part of. I know: if we talk about the temporary occupation of the WTC in Brussels, a lot of people have their doubts about what this meant in view of the current project, and we, to a certain extent, share these doubts. But it has been such an open ended experiment. There were a lot of things we learned. The most important thing is to realize that you will never be totally right, somehow. What I found sometimes annoying in the discussions afterwards was that people were trying to decide who is right and who is wrong. But that is a debate that doesn’t produce the type of value we are looking for.

Johan: One of our strategies is to work on a portfolio that is quite broad. It is not easy, it means that we go from almost pure real estate projects to landscape to social to cultural to public projects. To do so it’s important to understand the different perspectives on reality that exist. It is amazing that the lecture of all these projects is like doors to different rooms of thinking, of reality. It helps us to understand the complexity of how things can meet. Because that is in the end one of the purposes – to define common goals that can create a movement that somebody who is poor as well as somebody who is rich, somebody who is left or who is right can connect to. In that sense, yes, it is a political choice of what we try to do – to integrate diversity. It is the only way to create sustainable solutions.

TID Tower, mixed use, Tirana, Albania, 2016, photo: Filip Dujardin

TID Tower, mixed use, Tirana, Albania, 2016, photo: Stefano Graziani

ZIN in No(ord), mixed use, Brussels, Belgium, image: ArtefactoryLab

ZIN in No(ord), mixed use, Brussels, Belgium, image: ArtefactoryLab

ZIN in No(ord), mixed use, Brussels, Belgium, image: ArtefactoryLab

Profil

Freek Persyn and Johan Anrys are founding partners of architecture office 51N4E in Brussels. Their work ranges from internationally recognized projects in Belgium and abroad to open structures, architectural landscapes and projects that focus on processes and civic involvements rather than necessarily on the design of predefined buildings. The office itself has been partially nomadic, relying on temporary use of an architecture in transformation.

www.51n4e.com

Johan Anrys and Freek Persyn, © Photo: Pauline Colleu/51N4E